Image: The edge of Wistman’s Wood. This post is by Guy Shrubsole.

Update, 3rd July 2023: I’m delighted that the Duchy of Cornwall, working with their tenant farmer John Malseed and Natural England, have today announced a plan to allow Wistman’s Wood to naturally regenerate and expand – with a goal of doubling the size of this fragment of temperate rainforest by 2040.

Original post, 29th June 2021:

Visitors have recently been urged to stop walking through the middle of Wistman’s Wood, in order to help protect it. The move begs the question: when will sheep and cattle also be prevented from grazing in the iconic wood, so that it can regenerate and spread again?

Wistman’s Wood is Britain’s most famous fragment of temperate rainforest, one of only three surviving upland oak woods on Dartmoor – famous for its stunted and gnarled oak trees, lichens and bryophytes, and many associated myths and legends.

Far from being moribund, Wistman’s Wood in fact doubled in size between the 1880s and 1980, thanks to a combination of climatic shifts and a reduction in grazing pressures. But a subsequent apparent increase in grazing has halted the expansion and natural regeneration of the wood.

Whilst it’s vital that visitors to the wood treat it with the utmost respect, it’s clear that overgrazing poses a much bigger threat to its long-term survival. To enable Wistman’s Wood to regenerate, a fresh agreement is needed between the Duchy of Cornwall as landlord, the tenant farmer, and Natural England. This post makes the case for such an agreement.

Ownership and management of Wistman’s Wood

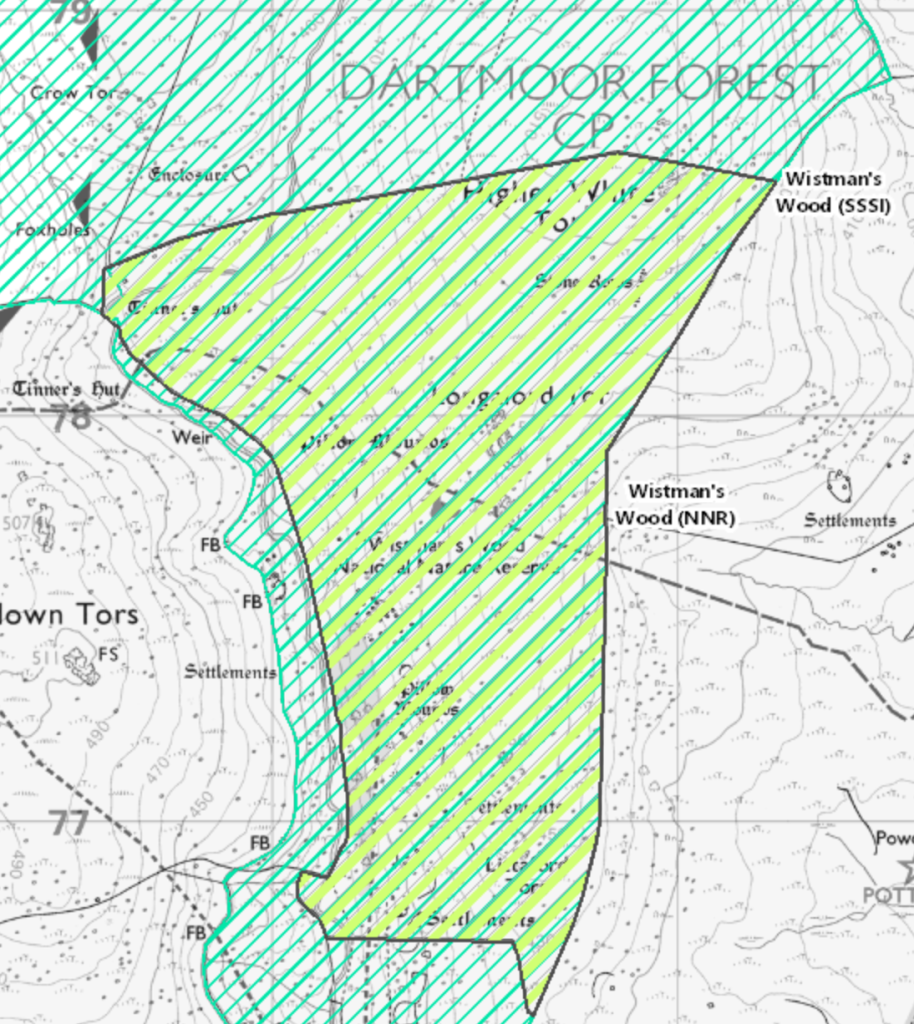

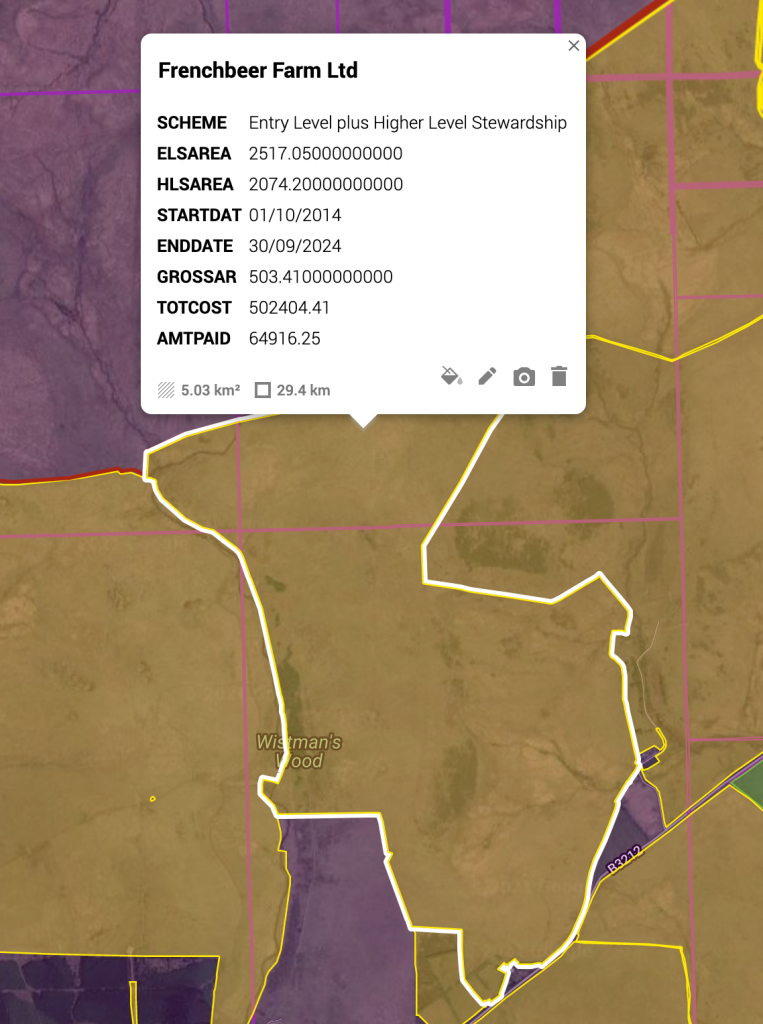

- Wistman’s Wood is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, and since the 19th century has formed part of an enclosure called the Longaford Newtake (enclosures on Dartmoor are all called ‘newtakes’). This means that common grazing rights no longer operate over the newtake, but livestock grazing still takes place by the sole tenant farmer (currently Frenchbeer Farm Ltd).

- In 1961 Wistman’s Wood and the surrounding Newtake were designated as a National Nature Reserve (NNR) and shortly afterwards as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), mainly for the rich lichen and bryophyte flora supported by the wood. Today, responsibility for maintaining the condition of the SSSI/ NNR lies with Natural England. As the SSSI notification for the site states, “With the exception of a small fenced area of the wood [a study exclosure], the whole valley is open to grazing by sheep, cattle and ponies”. An Environmental Stewardship agreement (brokered under the old CAP farm payments system) covering the whole newtake runs until 2024.

- Management of the wood is therefore a three-way relationship between the Duchy as landlord, the tenant farmer, and Natural England.

Right: Environmental Stewardship agreement covering the newtake with the tenant farmer. See also map of Dartmoor land ownership here.

Wistman’s Wood has doubled in size since the Victorian period – but regeneration has now ceased

- Wistman’s Wood is often portrayed as a moribund relic, but in fact various studies have shown the wood has grown dramatically in size in recent history. Proctor et al. (1980) demonstrated that the wood has doubled in size since the earliest photos taken in the 1880s, partly as a result of climatic changes (the end of the regional Little Ice Age in the mid-Victorian period and milder climate since then), but also because of changes in grazing pressures. Historical records and modern measurements by ecologists also suggest that the average tree height in Wistman’s Wood has increased considerably. Natural England’s webpage on Wistman’s Wood NNR notes the “woodland area doubling in size in the last 100 years.”

- However, Mountford et al. (2000) showed that more recent increased grazing pressures since the 1960s have slowed this natural regeneration once again, with young seedlings nibbled to the quick by livestock. A walk around Wistman’s Wood today will show you that there are hardly any young saplings outside of the study exclosure.

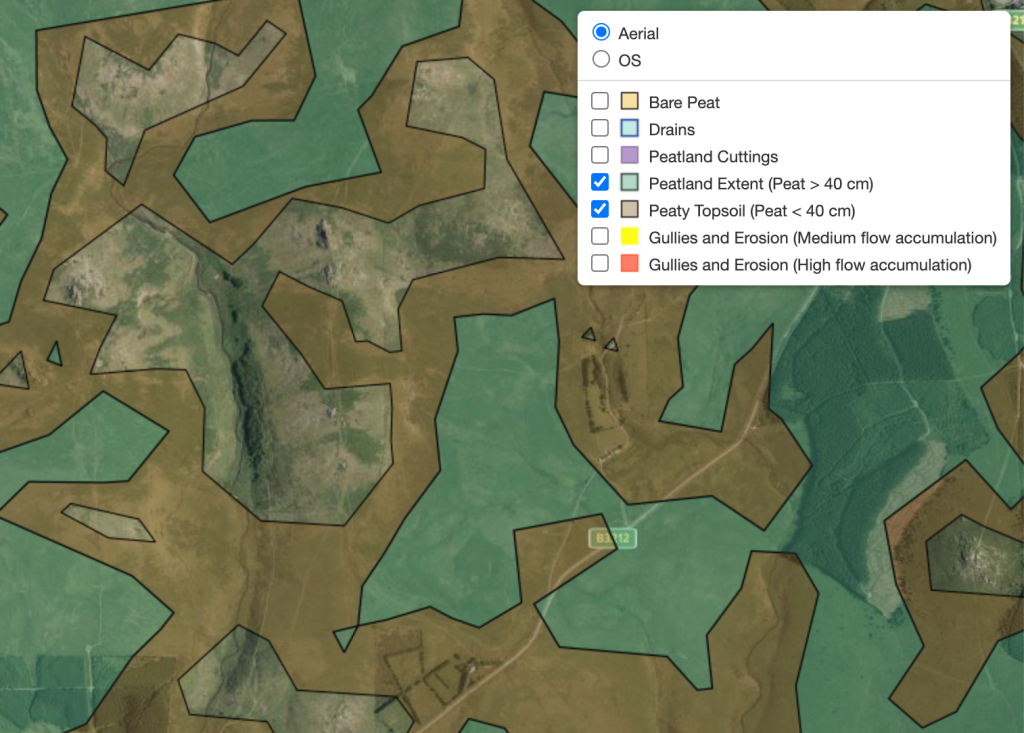

Dartmoor once supported more trees – and could do so again

- Pollen records and macrofossil evidence show that Dartmoor was once likely far more wooded than today (see e.g. IG Simmons, ‘Pollen diagrams from Dartmoor’, 1963; Maguire and Caseldine, ‘The Former Distribution of Forest and Moorland on Northern Dartmoor’, 1985). Whilst much of the subsequent deforestation took place as long ago as the Bronze Age, along with climatic changes leading to the formation of blanket bog, it’s likely that other small upland copses persisted on the boulder-strewn slopes of Dartmoor’s valleys and tors until more recent centuries, before succumbing to tin-miners and overgrazing. Amongst various accounts, William Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor (1909) records the former existence of a place called Fur Tor Wood on the now treeless slopes of Fur Tor in the middle of the moor.

- Natural regeneration of trees on Dartmoor’s mineral soils (outside the limits of its deep and shallow peat soils), on the slopes of various rivers and on boulder fields, is constrained currently by grazing pressures. Even so, there are numerous places on Dartmoor where natural regeneration can be seen to have taken place over the last 30 or so years: from the O Brook near Venford Reservoir, to the common of Lustleigh Cleave on the eastern edge of the moor, where cessation of swaling (burning) and a reduction in the number of active graziers has allowed a dramatic regrowth of oak and birch woodland in the last half-century.

Getting the grazing balance right

- There is a debate about the right level of grazing within Wistman’s Wood to ensure that rare lichens and bryophytes get sufficient sunlight to flourish. Whilst this is entirely legitimate, it appears that the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of overgrazing. This is shown by the lack of young saplings in Wistman’s Wood, and the halting of natural regeneration and spread that allowed the wood to double in area between the late 19th century and late 20th century.

- With grazing kept at current levels, it is hard to see how the wood can regenerate itself. But with grazing reduced, perhaps halted completely for a period of time, it could extend in size over the remaining bare boulder fields. This would be compatible with continued public access to the site, but would help buffer the wood against future damage from both tourists and livestock. One option might be to exclude or reduce grazing within the entirety of the walled newtake. An alternative is to install some fenced exclosures on the outskirts of the wood. Exclosures are used at other upland oakwoods to allow regeneration, for example at Piles Copse on southern Dartmoor, and at Yarncliffe Wood (Padley Gorge) in the Peak District.

Setting a precedent for bringing back Britain’s rainforests

If there were agreement for allowing Wistman’s Wood to regenerate and spread, it could have repercussions far beyond this one site. It would also encourage other farmers and landowners to allow the natural regeneration and expansion of similar temperate rainforest sites in the Westcountry, Lake District, Wales and western Scotland.

A three-way announcement by Natural England, the tenant farmer and the Duchy, signalling plans for the regeneration of Wistman’s Wood – and thereby Britain’s rainforest – could be a momentous occasion.

Please support regeneration of the wood by reducing grazing.

LikeLike

I wonder what Prince Charles, who is the Duke of Cornwall and owns the land, thinks of this proposal?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve known this wood all my life. Not sure what the current stocking level is, though I gather it is quite low so I imagine it may be more than one factor at play in terms of the lack of new growth. The wood doubled in size during a historical period when stocking numbers were higher than they are now so other factors are clearly at play. Oak doesn’t take up well under shade of oak and the exclosure within the wood proved this as very little, if any, regeneration took place there. There are many boulders in the open areas between each wooded patch and these can act as protection against grazing – there are in fact a few saplings hidden amongst them. But I think it is likely that the seed source is depleted at this site, either that or seed is not sufficiently transported. Regeneration is hugely dependent on the quality and abundance of seed as well as ground conditions. It is a complex issue which warrants deeper investigation.

LikeLike

Hi Em, do you have any stats to show that stocking numbers were higher in Wistman’s Wood between 1880 and 1980, during which time it doubled in size? There are no stocking figures cited in any of the ecological studies; I’ve asked the Duchy for any records they have, but not yet received a reply. I think the opposite is likely to be true: that the enclosure of Wistman’s Wood within a newtake reduced the stocking density, because it was no longer being grazed by multiple commoners, just by one tenant. The agricultural depression 1880-1940 may also have contributed to reduced stocking numbers.

The issue is also not really abundance of acorns or oak regeneration under the shade of existing oaks, but the inability of new saplings to survive germination once they’ve been carried outside of the woodland edge by jays etc: the fresh saplings that have germinated in the past are simply eaten by livestock, as the 2001 study shows.

LikeLike

Good response I think. I reckon that it may also necessary to stop the high footfall to these fragile sites. ELMS will I think also have an effect on sticking levels on the Moor.

LikeLike

Hi Guy,

Thank you the for the infomative article about wistsmans woods. I am a Masters student at the University of Exeter and have a group assignment focusing on temperate rainforests. We are particuarly going to focus upon wistmans woods, therefore, I was wondering if we could email some questions due to your expertise on the subject. It would be extremely helpful as gain a further understanding of the challenges facing temperate rainforests in the UK.

Alec Lee

LikeLike